Financial inclusion, especially providing services to those people and small businesses that traditionally avoided full-service banking, has long been a calling card for financial technology firms.

“We help drive innovation, inclusion, and access across the industry,” boasted Chime, which since its launch in 2013 has emerged as one of the largest so-called neo-banks.

Interest rates near zero and an untapped market of millions of adults helped the industry flourish, from financial services firms to cryptocurrency startups.

But inflation and rate hikes have slowed new funding to a trickle. As investors’ push for profits grows, so too does concern that fintechs will abandon their pledges to cater to the underserved.

Consider the online bank Varo Bank, which raised $510 million and boasted a $2.5 billion valuation last September. Then, like many fintechs, it hit a wall in 2022.

With losses mounting, it laid off 75 staffers, cut back on advertising and shifted strategy, moving away from growing its total client base and shedding what CEO Colin Walsh called “expensive customer acquisition” in an interview this month with Axios.

Those expensive customers usually end up being from Black, brown and other marginalized communities that cost more to reach and generate the lowest revenues, said Mehrsa Baradaran, a professor at the University of California Irvine School of Law and author of the book “How the Other Half Banks.”

“Once you’re being squeezed on every end, clearly the least profitable are the first to go,” she said.

Acting Comptroller of the Currency Michael Hsu highlighted the issue this month at a Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia fintech conference.

“The story’s changing now. The story’s now about profitability. It’s about unit economics,” Hsu said. “Where is the inclusion in that?”

Usually Unprofitable

About 80 percent of American adults use a full-service bank, but a report released this week from Congress’s Joint Economic Committee found that 40% of Black Americans, 29% of Hispanics and more than 33% of households earning less than $25,000 per year are still unbanked or underbanked.

Those consumers were part of the market many fintech startups targeted in the past decade. But they really caught venture capitalists’ eyes beginning in 2018.

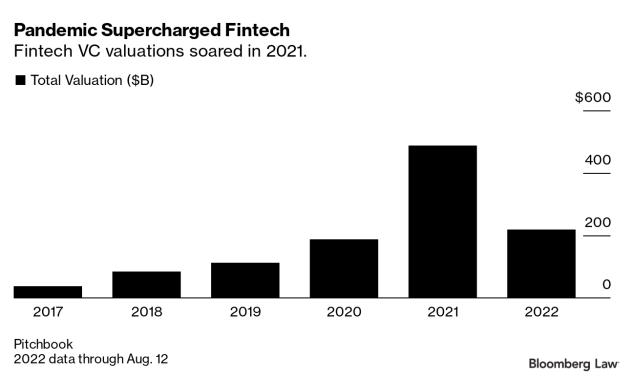

Venture funds pumped $14.7 billion into 1,131 fintech deals with a total valuation of $83.9 billion 2018, according to Pitchbook, a firm that tracks venture capital investments.

That jumped to $55.2 into 2,058 deals with a total valuation of $488.4 billion in 2021, Pitchbook found. The pandemic caused a “shift to moving online and fintech was a huge beneficiary of that,” said Robert Le, a Pitchbook fintech analyst.

That new funding has since fallen flat, as the Fed raised rates and inflation spiked. According to Pitchbook, money for fintechs plummeted from its breakneck pace through the first half of this year, with 1,181 deals valued at $18.8 billion through July.

And those already up and running began scaling back. Klarna, a privately held Swedish BNPL and consumer finance company, announced plans to lay off around 10% of its workforce in May, after its valuation dropped by more than half in the beginning of the year.

Chime in February confirmed plans to delay its hotly anticipated initial public offering, citing the collapse of fintech stocks and valuations of private financial technology firms.

The tumbling private valuations mirrored the collapse of many publicly traded fintechs. One example is buy-now-pay-later firm Affirm Holdings Ltd., which saw its stock collapse in the first half of 2022, down as much as 60% by April.

The other problem that fintechs encountered is that, at this point early in their existence, many aren’t yet profitable.

“Fintechs are by definition growth companies, and venture-backed fintech organizations are usually unprofitable,” said Joe Zhao, a managing partner at Millennia Capital, a venture capital fund focusing on fintechs.

Pension funds, family offices, foundations and other institutions that contribute to venture funds are starting to look for more sure-fire investments rather than riskier plays with fintechs and other startups, Zhao said.

“I’ve had conversations with portfolio company CEOs and CFOs, telling them you need to cut costs,” Zhao, a former Fed economist, said.

The first cuts come to marketing budgets. If those aren’t sufficient, fintechs and other companies will start cutting staff. Several fintechs and crypto firms, like Varo Bank, have announced thousands of layoffs this year.

Jonah Crane, a partner at the Klaros Group, a financial services advisory firm, said the trend could lead to additional customers being dumped because an acquiring firm is only interested in the tech part of a fintech, or their data getting used in ways customers didn’t intend.

“You could have a situation where consumers’ data becomes the only thing to monetize, and the data may end up in places maybe they never anticipated,” Crane, a former Obama Treasury Department official, said.

A Focus on Core Customers

The fintech fallout ripples in other ways.

Brex, a San Francisco-based fintech, had launched in 2017 with a focus on venture capital-backed startups, primarily in the biotech and fintech industries. Airbnb was one of its early clients.

As operations grew, Brex began serving traditional small- to medium- businesses, like restaurants, retailers and independent operators like Debra Gail White.

White, a Los Angeles musician, turned to Brex in 2020 for a corporate credit card and payment services for her small record label, 27 Club. The services came without any fees—Brex makes its money off interchange fees from retailers and recurring fees for software subscriptions—and worked reasonably well. White says between processing payments and using the corporate card, she ran around $100,000 through Brex over the course of two years.

Then the pandemic, inflation and the Fed’s interest rate hikes took a toll. Brex doesn’t appear to have a funding problem—it had a valuation of $12.3 billion at its most recent funding round in October—but realized some of its original startup clients might.

In June, Brex said it would drop thousands of small businesses from its platform to focus on its original and core clients.

Brex cofounder Pedro Franceschi in a tweet called it “an incredibly difficult” decision. “We learned we couldn’t serve smaller businesses well at the same time, and focus was the only way to deliver a level of service we’re proud of,” he wrote in a blog post.

White says she would have been willing to pay service fees to stay with the platform, but presumes that “it’s faster and cheaper” to drop customers like her.

CFDI’s Fill the Gap

Fintechs insist they’re going to keep pushing for greater financial inclusion even in the tighter financial climate. For some, the business model demands trying to get more customers, which should boost services to marginalized communities.

Companies like

And venture-backed firms with growth business models won’t have a choice, Pitchbook’s Le said.

“If you’re Chime, you can’t say that you’re not going to serve lower-income customers, because that’s their bread and butter,” he said.

Even as fintech valuations have plummeted, Chime has expanded its offerings to include allowing customers to deposit cash into Chime accounts at more than 8,500 Walgreens Inc. stores around the country in June.

But other lenders are getting prepared for fintechs to cut back, particularly small business lenders.

Preparing to fill the breach are community development financial institutions—small, community-based lenders that focus on providing funding to largely women- and minority-owned small businesses with less than $1 million in revenue, said Patrick Davis, the senior vice president of strategy at Community Reinvestment Fund USA.

The Biden administration has committed more than $1 billion accessible through CDFIs for the smallest startup businesses. Banks have also been increasing their contributions to CDFIs with the express goal of getting money to hard-to-reach small businesses.

“Fintechs won’t look at those startups at all,” Davis said. “CDFIs will.”

Source : From the Web